Wandering between fields

In my last two contributions to the blogposts of the RELEVEN, the readers might have noticed that I was progressively gravitating to the matters of Central Europe. My work on the Byzantine material is mostly done. After participation on several conferences and workshops until July, late summer and autumn were primarily spent collecting data in relation to Central Europe. In truth, I also prepared some papers for publication in the meantime, but I have already talked about their topics. Therefore, I am leaving aside this part of my efforts, and I am concentrating on the data in this post. I had two major assignments in the last few months. First, I collected prosopographical data from eleventh-century sources from the Holy Roman Empire. Second, I had to read through some literature on the archaeology of the aforementioned region in order to help the data modelling of archaeological evidence in the RELEVEN database. Before I move to the main topics of this post, I would like to mention my paper I gave on the international conference “Byzanz und das Abendland IX.” in late November. I talked about how our project and the STAR model would contribute to the Byzantine studies. The project apparently attracted the interest of the audience as I got more questions after this presentation than usually.

Central Europe in German sources

What is the significance of “German” historical literature in the analysis of eleventh-century Central Europe? Central Europe or more precisely Eastern Central Europe, namely Bohemia, Hungary and Poland, was in a particular situation in the eleventh century. Although they began Christianisation in the 950s and 960s, their societies were still in transition into Christian communities in the following century. Before the adoption of Christianity, all the polities had vocal societies without significant written culture. It took a long time that a literature dominated by Latin developed in the region. Consequently, Central Europe initially lacked its own production of written records. The chronology of this progress differed by each polity, but it was common in the region that historical writing appeared only in the last decades of the eleventh century or even later.

Therefore, if one intends to find contemporary historical narratives about Central Europe, it is necessary to search in the neighbouring areas, especially in the Holy Roman Empire. By the eleventh century, the old East Frankish Empire had long tradition of historical writing flourishing in different genres. The disadvantage of this source material is that all the works in question obviously focus on the matters of the German territories. Central Europe is represented in an unbalanced manner, from an imperial perspective. However, the interests of the different authors and compilers apparently varied in details. For example, the Annals of Niederaltaich provides us with an account of the war between Conrad II and Stephen I in 1030, which is different from many other narratives, notably the description in Gesta Chuonradi II by Wipo of Freising. The disagreement between these sources about the event is significant at some points, since one can make various reconstructions of the movement of people according to the accounts. The Annals of Niederaltaich states that Henry III, son of Conrad II and then the heir of the Holy Roman Empire, visited Hungary as an envoy in order to negotiate with Stephen I on peace in 1031. Meanwhile, the Gesta Chuonradi II suggests that Hungarian emissaries approached Henry III (probably staying in Bavaria) to arrange a peace treaty between the two powers. This kind of discrepancies in the source material are exceedingly important to the RELEVEN project, as one of our main goals is the representation of differing authorial voices on the same events.

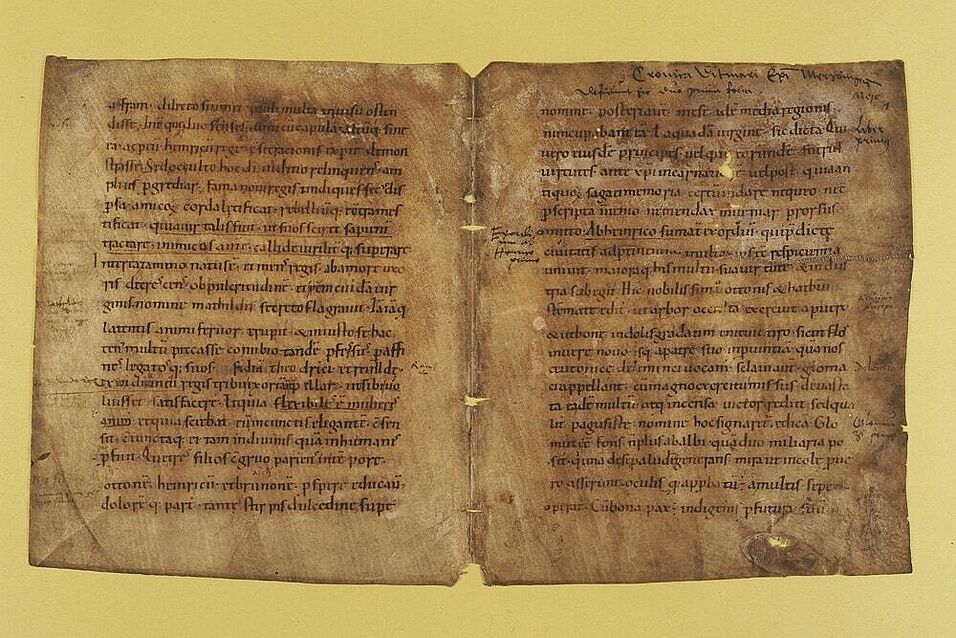

Therefore, I surveyed several historical works from the Holy Roman Empire, and collected historical data, which were connected to Central Europe, from c. 1000 to 1050. The list of the analysed works includes the Annals of Hildesheim, the Annals of Niederaltaich, the Chronicon of Thietmar, the Gesta Chuonradi II, the Chronicle of Herman of Reichenau, the Chronicle of Lambert of Hersfeld, and the Chronicle of Frutolf of Michaelsberg. The collection of data is primarily prosopographic in its nature, and I specifically searched for information about the spatial movements of individuals, as it is the main focus of my personal research in the project. The final dataset contains 913 separate entries, from which around 600 are from the recent investigation after August 2023.

Archaeological sources

Since written sources from (Eastern) Central Europe are scarce, when one focuses on eleventh century, the significance of archaeological evidence increased in the last few decades. However, the historical interpretation of archaeological data has its perils, and, not surprisingly, there are notable differences between historians and archaeologists in their approach to this material.

Due to my responsibility for the historical data on Central Europe, I had the task of analysing secondary literature on archaeology. The main objective of this work was to find data on archaeological findings, which can be included in our RELEVEN database. I also had to observe the question for which aspects of our research we can use this material. Fortunately, I could use a selected bibliography collected by Nina, our archaeologist, during my short investigation.

In truth, archaeological evidence posed a challenge to me for different reasons. The project focuses on the eleventh century, but the dating of archaeological evidence often does not correspond to this chronological limit. It is usual that an artefact found during an excavation is dated to a wider period such as, for example, the early Árpádian era (1000–1250). Many archaeological objects or findings should be ignored in our analysis due to their vague periodisation even if there is a possibility that some of them were produced or used in the era of our interest. Another problem was the different approaches of the literature to handle the archaeological data. Some studies gave good overviews about specific topics, but often lacked any reference to individual artefacts, which would be a basis of my data collection.

The use of archaeological data in our project is an interesting problem. The key is the information about parallel objects found in different regions. Of course, the interpretation of the parallels is another issue. Nevertheless, trade and economic connections can be detected in the background in most cases. At the same time, parallels between separate buildings across Europe may imply the movement of architects and other related craftsmen. Sporadically, some findings reveal information about real movement or spatial mobility such as the graveyard of Rus’ individuals in Bodzia.

I also consulted Maria Vargha, an expert in the archaeology of Medieval Central Europe, about this matter. She warned me that pottery as archaeological evidence would be less useful for our project, especially for the issue of their dating. Therefore, we will shift our focus onto other type of artefacts.