The main research object of the project is the eleventh century in the Christian world. As my purview are Byzantine Greek sources, in this monthly blog post I will attempt to explain why we deal with eleventh century in Byzantium in particular and why this period is an intriguing and fertile area for historical research.

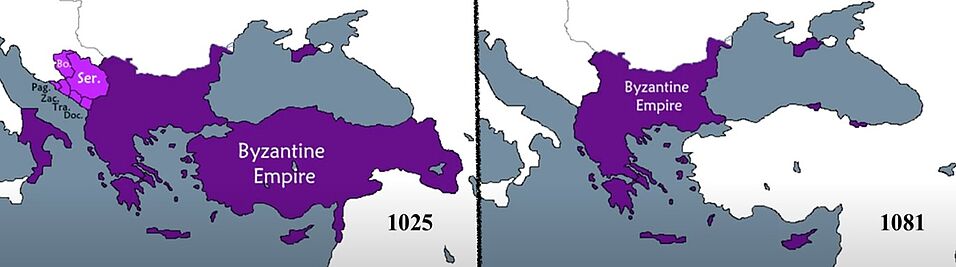

The late tenth and the eleventh centuries in Byzantium have often been acknowledged, and rightly so, as “the pivotal period in Byzantine history” (Kaldellis 2017, xxviii). Especially the “short” eleventh century, that is, the period between the death of Basil II in 1025 and the rise to power of Alexios Komnenos in 1081, saw significant shifts in terms of the political and economic circumstances of the Empire (Angold 1997, 99-114, Haldon 2009, 191-2, Bernard 2014, 10-17, Kaldellis 2017, 154-270). Both Basil II and Alexios Komnenos have been viewed as strong military figures consolidating the Empire’s stability (Stephenson 2003, Angold 1995), whereas as many as thirteen emperors and empresses in between witness the fragility of the imperial power and a tumultuous Kaisergeschichte. In addition, during 1025-1081, the Empire faced territorial vulnerability, external threats, internal military uprisings, and religious conflicts. Something obviously “went catastrophically wrong in the third quarter of the eleventh century” (Kaldellis 2017, 271).

Firstly, starting with – in modern scholarship still the notorious – battle of Manzikert in 1071 and the gradual Byzantine territorial losses in Anatolia from which the Empire never fully recovered in the east (Cheynet 1980), to the conflicts with Pechenegs in the Balkans and Alexios Komnenos’ troubles with the Normans in the Adriatic area, the territory the Empire effectively controlled by 1095 was only a small portion of what Basil II left to his fellow Byzantines in 1025.

Secondly, the attempted coups d’état over a short period of time, e. g. those by Georgios Maniakes, Leon Tornikios, and Isaakios Komnenos (Cheynet 1990, 57-60, 337-339) strikingly point to internal instabilities and an extremely fragile imperial power in the period under investigation. Thirdly, this is a period that witnessed troublesome dogmatic politics and ecclesiastical tensions too, both within Byzantium itself and between Byzantium and its neighbors. In terms of ecclesiastical politics and religious tensions, Byzantine eleventh-century is thus the most well-known for the grand narrative of the Church schism between east and west in 1054, an event that has traditionally been seen as the break between east and west. However, its developments and significance are being rethought and reevaluated in modern scholarship, (Bayer 2004, Ryder 2011, Kolbaba 2011, Cheynet 2017); especially the mobility and travel between east and west in the eleventh century have been singled out, both before the “schism” (Shepard 2017, 129) and after, where, for instance, Amalfitans from Italy had their quarter and a monastery in Constantinople after 1054, which is an example of what RELEVEN aims to explore. Furthermore, religious tensions can be reflected in the numerous charges and trials of heresy in this period, either on individual or on a collective level, from the Bogomils in the northwest to the Jacobites in the southeast (Angold 1995, 19-21). Finally, major transformations in the religious, political, territorial, and diplomatic state of affairs of the Byzantine Empire will lead to the First Crusade in 1095.

What happened and why then? Historians interested in political and military history attempted to answer these questions and explain the alleged apogee-collapse situation in this intriguing period of the Roman politeia. At first, the discrepancy between what was viewed as the “apogee” of the Empire under Basil II that ended with his death in 1025 on the one hand and the territorial losses after the battle of Manzikert and 1071, led scholars such as Ostrogorsky to view mid-eleventh century in Byzantium as a period of decline (Kazhdan 1992, 111-124), explaining it as the outcome of internal conflicts within the Empire, namely between the bureaucrats from the capital and the landowners and military magnates from provinces, mainly from Anatolia. In other words, Ostrogorsky and like-minded scholars have viewed the transition into the medieval-western-style “feudalization” as the main cause of the alleged decline. Shortly afterwards, the Gibbonean model of rise, decline, and fall of a society has been questioned, in this particular case primarily by the French school of Byzantine studies (Ahrweiler 1976, Lemerle 1977), who instead interpreted the period 1025-1081 as the time of full-scale transformations – social, cultural, and political – yet still stressing the endogenous issues as the causes of the collapse. These were followed by a research of a Marxist historian Kazhdan, who likewise advocated for the Byzantine eleventh century as a transitional period, at the same time singling out Byzantium’s internal class struggles, emphasizing the process of “feudalization” in eleventh-century Byzantine society (Kazhdan & Epstein 1985). More recently, Kaldellis (2017) has criticized the theory of “feudalization” and Constantinople’s inner conflicts with provincial magnates as the main cause of the territorial losses, and proposed instead a more detailed analysis of the plans, strength, and strategy of Byzantium’s external adversaries such as Seljuks and Normans, thus focusing on exogenous causes of the collapse. Finally, most recent scholarship has interpreted the change in eleventh-century Byzantium by attempting to find answers in socioeconomic aspects such as urbanization, economic reforms, and military history, as well as in climate change (Haldon et al. 2014, Howard-Johnston 2020).

Whether it was a decline or a transformation, it is clear that eleventh-century Byzantium presents an impressive case study for historical research for two major reasons. First, the vast variety of eleventh-century narratives as primary sources allow us to observe and trace various developments such as, for example, literary trends or monastic reforms, side by side with unprecedented frequency of internal and external upheavals. And second, the twentieth-century and most recent scholarship on eleventh-century Byzantium indirectly reflect a connection between scholarly intellectual trends and ideologies on the one hand and the kind of tools and projections scholars today use – be that historicist, Marxist, postmodern, or modern – when exploring and explaining the state of affairs in the Byzantine Empire a millennium ago.

References:

Ahrweiler 1976 = “Recherches sur la société byzantine au XIe siècle: nouvelles hiérarchies et nouvelles solidarités,” Travaux et Mémoires 6 (1976): 99–124.

Angold 1995 = Church and Society in Byzantium under the Comneni. Cambridge: CUP, 1995.

Angold 1997 = The Byzantine Empire, 1025–1204. A Political History. New York: Longman, 1997.

Bayer 2004 = Spaltung der Christenheit. Das sogenannte Morgenländische Schisma von 1054. Köln: Böhlau, 2004.

Bernard 2014 = Writing and reading Byzantine secular poetry, 1025-1081. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

Cheynet 1980 = “Manzikert: un désastre militaire?“ Byzantion 50 (1980): 410-438.

Cheynet 1990 = Pouvoir et contestations à Byzance (963-1210). Paris: Université de Paris, 1990.

Cheynet 2017 = “Le Schisme de 1054: Un Non-Événement?” In Faire l’événement Au Moyen Âge, ed. Claude Carozzi and Huguette Taviani-Carozzi, 299–312. Aix-en-Provence: Presses Universitaires de Provence, 2017.

Haldon 2009 = Social History of Byzantium. Chichester: Willey-Blackwell, 2009.

Haldon et al. 2014 = “The Climate and Environment of Byzantine Anatolia: Integrating Science, History, and Archaeology,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 45 (2014): 113-161.

Howard-Johnston 2020 = Social Change in Town and Country in Eleventh-Century Byzantium, ed. J. Howard-Johnston. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Kaldellis 2017 = Streams of Gold, Rivers of Blood: The Rise and Fall of Byzantium, 955 A.D. to the First Crusade. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Kazhdan & Epstein 1985 = Change in Byzantine Culture from the Eleventh to the Twelfth Centuries. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

Kazhdan 1992 = “Russian Pre-Revolutionary Studies on Eleventh-Century Byzantium.” In Essays on the Slavic World and the Eleventh Century, ed. S. Vryonis, 111-124. New Rochelle: Caratzas, 1992.

Kolbaba 2011 = “1054 Revisited: Response to Ryder,” BMGS 35 (2011): 38–44.

Lemerle 1977 = Cinq études sur le XIe siècle byzantine. Paris: Centre national de la recherche scientifique, 1977.

Ryder 2011 = “Changing Perspectives on 1054,” BMGS 35 (2011): 20–37.

Shepard 2017 = “Storm Clouds and a Thunderclap: East-West Tensions towards the Mid-Eleventh Century.” In Byzantium in the Eleventh Century: Being in Between, ed. Marc D. Lauxtermann and Mark Whittow, 127–53. Abingdon: Routledge, 2017.

Stephenson 2003 = The Legend of Basil the Bulgar-Slayer. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.